The Diary of a Pastor’s Wife

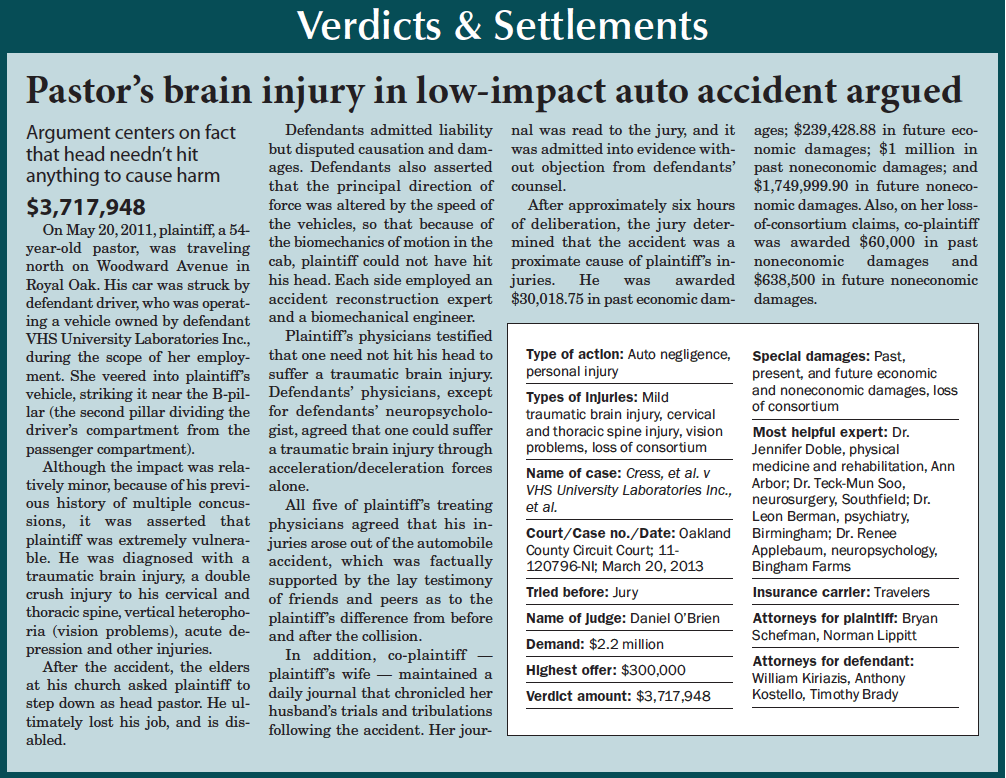

Journal of man’s struggles was key to $3.7M recovery By Douglas Levy After a pastor was injured in a lowimpact auto collision, his wife kept a daily journal about how his day-to-day activities had changed following the wreck. That journal was the key evidence in an Oakland County case where the jury awarded the couple $3.7 million.

At issue in the auto negligence suit was the pastor’s vulnerability to a head injury. He had suffered four prior concussive events in his life, and the defense argued causation and damages from the crash.

Bryan Schefman, a Bloomfield Hills attorney, explained that his medical experts on the stand testified that the plaintiff’s traumatic brain injury, among other injuries, was caused in the accident. But the wife’s perspective, as chronicled in her journal, filled in specific details of how the pastor’s injuries factored into his life.

“It’s one of the reasons we ask clients to keep them,” Schefman said. “They cannot be expected to recall —especially under the stress of testifying live on the stand — the little details of ordinary life and how they’ve become impacted by an injury.

“So we ask clients to keep a diary so they have a present recollection, a present record of every little thing that impacts them as a result of their injury.”

Question of Causation

In the May 2011 accident, the defendant driver struck the pastor’s car near the B-pillar, the portion of the auto that separates the driver’s compartment from the backseat passenger compartment.

Though the defendants admitted liability, they argued that the force of the impact could not have caused plaintiff to hit his head. But plaintiff’s physicians countered that one need not hit his head to suffer a traumatic brain injury, and defendants’ experts — with the exception of a neuropsychologist — agreed that acceleration/deceleration forces are sufficient to cause TBI.

Schefman said the experts’ testimony was in accordance with Centers for Disease Control testimony to U.S. Congress over the issue, as well as what the American College of Rehabilitation Surgeons has in its annals of research.

Further, Schefman said, four incidents in plaintiff’s life — two in high school, one in military and one five years ago — all involved loss of consciousness, creating “a cascade effect” of vulnerability in a minor accident.

“A lesser impact may not have caused this injury in anyone else, but for this individual, it did, and the reason it did is, the brain lost its capacity to compensate,” Schefman said. “So even their experts all admitted there would be decreased capacity to compensate on a successive event, and successive events have a cumulative effect.”

The accident also caused a double crush injury to the plaintiff’s spine, vision problems and acute depression. Schefman’s co-counsel, Birmingham based Norman Lippitt, added that defendants’ experts were using engineering terminology and arguing about principle direction of force.

To counter that before the jury, he said he used simple analogies, because to do otherwise, “you’re really escaping the obvious. If you don’t live in Africa, and you hear hoof beats, you don’t look for zebras, you look for horses. I did things like that.” ‘Very peculiar’ jury mix Plain talk was crucial, said Lippitt, who did voir dire, closing arguments and rebuttal, because the jury was a“very peculiar” mix.

Six out of the eight jurors were between 22 and 24 years old, as they were students on midterm break from college. And three of the jurors were engineers or engineers in training.

“People will tell you, if you’re a plaintiff’s lawyer, you don’t want engineers on your jury. They’re too technical, too detailed,” said Lippitt, who is a former judge. “You want people who are more sympathetic. But this jury was very logical.”

Before closing arguments, Lippitt said he spoke to a patent attorney at his firm and her husband, who’s a mechanical engineer, to get their take on the case. This gave plaintiff’s counsel a better way to get the jury to understand the case.

But plaintiffs’ counsel still needed to explain how such a low-impact incident could cause a high-impact impairment. So, immediately after their first meeting, which was two weeks after the accident, Schefman asked the pastor’s wife to detail his day-to-day struggles.

The wife was a co-plaintiff, and her journal described her husband’s difficulty in coming to grips with his physical, emotional and cognitive limitations.

“We did have some difficulty in getting her to be forthright about her own impact — the impact her husband’s injuries had on her,” Schefman said. “The journal focused on her husband as opposed to her, and it could and should generally focus on both, but it’s very difficult for people to put their feelings down on paper.”

The journal was admitted into evidence, and it was published for the trial members to follow along with while plaintiff’s wife read from it in direct testimony. Schefman said it helped the jury understand who he was before the injury and who he was after the accident.

For example, he couldn’t read more than 10-15 minutes, he couldn’t teach the same way in bible classes, and he was asked to step down as head pastor because of his physical and mental disabilities. “That was the end of his life,” Lippitt said, on the church’s decision to retire him.

Preparedness and appeal

The jury deliberated for approximately six hours before determining that the accident caused the plaintiff’s injuries. The award was broken down as $269,448 in economic damages and $2.75 million in noneconomic damages for the plaintiff; while the plaintiff’s wife’s loss-of-consortium claims netted $698,500 in noneconomic damages.

William Kiriazis, lead counsel for the defendants, said it was too early to determine whether the case would be appealed.

Besides the journal, Schefman said he would tell other attorneys who might handle a similar case that no substitution for preparedness, such as dragging out the medical texts and being fluent in all of the medical issues.

“Be prepared to address issues well in advance — you have to see them coming,” he said. Lippitt added that the jury must like the plaintiff. “I represented the perfect family,” he said. “They were marketable. They were honest. They had integrity. They had jury appeal.”